by Sneha Sharma | Sep 6, 2021 | Book Discussions

A Room of One’s Own by VIRGINIA WOOLF

What is the book all about?

Following a mentor’s suggestion to read autobiographies/memoir of the heroes to capture the intricacies of their lives and learn the lessons they did the hard way, I came across ‘Room of one’s own’ – which wasn’t autobiographical but rather a literary critical essay on women fiction writers during 1920s. It falls under highly recommended reading for artists, literature history lovers, students of English literature, women writers and in general for all those simply needing an inspiration to write. Virginia Woolf, after a thorough research on women and fiction wrote this book as a ‘stream of consciousness.’

Why read it in today’s times?

As a piece of feminist writing, focusing on the problems of a woman writer belonging to a previous era, is the book worth reading?

Woolf’s use of language and intelligence has been highly influential on English literature and she is one of the foremost modernist literary figures of the twentieth century. For the writers learning to polish their strokes, not only reading but a study of some of Woolf’s work certainly proves valuable.

This book in particular talks about the genius of Bronte sisters, about English novelist George Eliot, how brilliant these writers were to be able to perform and produce sheer pieces of brilliance, working in extreme constraints, even hiding the fact that they were writing fiction, frightened to express their fondness towards the art, covered their writing with a blotting, for the shame of wasting their time with “scribbles” being a woman (as Jane Austen did whenever someone came into the common room), wrote in the living room with thousand practical distractions, ten children to look after, as the line was so predominantly considered a male profession.

George Eliot had to write under a male title for acceptance of her work. These harsh facts open our eyes to the atrocities that women writers and women in general faced as a fairer sex in Woolf’s era and prior. As an Asian community, the revelations surprise us because for us the West has always stood for freedom, expression and liberty and the violence and injustice done to women even if in a different era, the kind still prevalent in Indian societies, makes the read relevant enough for the artists and their male and female counterparts.

A female writers’ essential space

With the imaginary example of William Shakespeare’s sister, assuming she is equally talented as him, Woolf reasons, it’s not the difference of physical strength that had led historically, more work of writing from men than women. Her analysis of old literature and the basic gender roles discovers that men are at an advantage of space, money and education. In her quest to conquer the literary world of 16th century, this imaginary character of Shakespeare’s sister is blocked at every step by the society for being a female aspirant of writing.

So, it raises a point that for such female aspirants of writing, independence and solitude are essential for artistic creation. She needs a room of her own, money to buy herself that and a lock on the door.

The Conclusion

The conclusion of the book does satisfy the believers of feminism –

“It would be a thousand pities if women wrote like men, or lived like men, or looked like men, for if two sexes are quite inadequate, considering the vastness and variety of the world, how should we manage with one only? Ought not education to bring out and fortify the differences rather than the similarities?”

She also concludes that each human has a multifaceted personality and that each artist must draw from both male and female parts of the mind.

“In each of us two powers preside, one male, one female… The androgynous mind is resonant and porous… naturally creative, incandescent and undivided.

And most importantly she insists to write freely without any fear of judgement.

Relevance of the text to a modern female writer

Apparently what appears to be a minor attribute – having a space of one’s own, raised in the context of women writers’ quintessential need, something that a modern female writer might choose to laugh at -becomes a thought of serious consequence.

The space here has metaphorical context of literal-physical and mental arrangement a woman needs to write well. She needs to be free from the anxiety about the eligibility and trustworthiness of that ‘someone’ who is looking after her kids and household while she writes, at least till the time her children become independent. That’s when she can completely surrender to the world of her creative abilities and the magic it begets. A modern female writer too cannot choose to laugh at this one after all, as the problem is still very much relevant for her.

My personal account

When I wrote only as a hobby, I had to many times hide the fact that I am writing for the fear of being caught in doing something menial, something that is not paying one in money. I waited for the room to be empty as directly telling someone to leave for my writing in private, might be considered hysterical. I couldn’t design my own time and in stead my time of writing was decided at the mercy of others. I never openly discussed with my family how writing relieves me and is so beyond a hobby. When I started writing for Times and took to teaching as a job, many times in the alibi of working for my employers, I wrote my heart out. My excuse was now eligible for consideration.

Few years back although, during one of our evening walks, I explained to my husband and my sister, how imagining my routine days without some pleasure writing, would be difficult for me and how the regret would hover around when I am older, they took my earnest appeal in consideration and not only could I make time for doing what I loved to do but stood tall with motivation (motivation was never something I thought I would be needing so much because of the lapse in practice!).

While it might not be so simple for many other female counterparts, it still makes sense to discuss about one’s passions and desire to pursue a hobby, and if it is writing, about the ‘space’ one very much needs for her muse.

This book can give confidence to so many women wanting to express their unheard voices through their ink.

Suggested Further reading –

Analysis of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own

by Sneha Sharma | Jul 15, 2021 | Children's Literature

The world of children’s literature fascinates me and I many times find myself immersed into it. I read out to my kids, popular works of classic and contemporary Indian and American writers. Blessed with an audience of intent listening, it’s not just reading but lots of answering too, to their obvious and logical curiosities, which mark my fun time with my little listeners.

This week we decided to pick Rudyard Kipling’s Rikki-Tikki Tavi– the famed tale of a valiant mongoose who fights for his master with a deadly snake and his wife, Nagaina.

The story quickly got us hooked and was read out in a single sitting, without any break.

But my own curiosity of knowing behind-the-scene anecdotes and analysis of almost every story that I like, takes the course of some research. I found there were innumerable analytical essays and research submissions in renowned journals written on this enchanting story of Kipling.

Rudyard Kipling was known for his imperialist agenda, which also seeped into his stories and poems. Rikki-Tikki Tavi, if we note the symbolism behind it (which is hard to ignore), brings this agenda into the fore. The hero mongoose, on a second look is then reduced from a brave heart to a loyal colonial subject of imperialism and the narration thus implies the saving of an economically downtrodden India at the mercy of compassionate Britishers.

Take up the White Man’s burden–

Send forth the best ye breed–

Go, bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need;

On fluttered folk and wild–

Your new-caught sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child.

– Kipling, “The White Man’s Burden”

Post-colonialism refers to the period when the colonizers leave the country of their rule and return to their homelands, leaving behind significant trails of their culture and influence in the colonies. The story is set in that era as a backdrop as it was written during that time. The white couple portrayed in the story represents the Britishers who proclaimed to help the ‘uncivilized’ or the ‘heathens’ (adherents of a religion that does not worship the God of Judaism, Christianity, or Islam.) by staying amongst them, apparently to help these underdeveloped countries deal with famine, provide medical aid and make them more ‘civilized.’ Kipling saw the British Empire as a means to establish the groundwork for civilization in countries like India, but not without lifting its image to the appellation of a culture superior to the rest.

Many consider him a victim of naivety and idealism because of his extreme opinion and the superior notion about his culture.

This story is without much evidence to support the attribution of evil to Nag and Nagaina, with the adjectives like ‘Black’ and ‘Wild’ describing their negative character. Their negativity in the story emerges on the grounds of law of the land which requires punishment to someone who kills. This reflects narrator’s subjective bias. Since the law of nature governs the snakes, the characters can’t really be considered negative. They can be considered threatening to the humans in the bungalow, but not idealistically villainous as the snakes considered humans threatening too for their eggs. Also, when we read more about Kipling, we can’t help but notice how the character description of Nag and Nagaina, resonate so much with the ideologies of his culture’s superiority.

Tacking advantage of the personal enmity between snake and mongoose and on account of the perks the Mongoose foresaw in being faithful to its masters, as instructed by its mother, he story makes the owners keep the mongoose as a guard against the snake and a playmate for their child, symbolic of the Indians whom the Britishers picked as their loyal subjects.

This revelation was heartbreaking. However, the innocent curiosity of children remains unaffected, to simply know what happens ahead in this enchanting tale of a valiant mongoose guarding a family, which saved it from drowning and dedicates its life to their safety and guard. And with Kipling’s magical skill of hooking his audience with his splendid supply of imagination, it would have been unfair to keep the children deprived of devouring his work.

by Sneha Sharma | May 27, 2021 | Book Discussions

Elements of Gothic Symbolism.

The word ‘Gothic’ originated from a music category with dark morbid lyrics. In literature, Gothic fiction refers to the one exploring the elements of fear (even horror – haunted castles/homes), death and gloom and the romantic elements of nature, individuality and high emotion.

The protagonists of such novels are usually Gothic heroes, who are hard-core romantics (Gothic and romance are intricately related)

Edgar Allen Poe’s poem ‘Annabel Lee’ or ‘The Black Cat’ and works of Charles Dickens, Mary Shelley’s Frenkenstein, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray are other examples using Gothic symbolism.

It includes mystery and suspense, (burials, ghosts, flickering candles etc. Ann Radcliffe’s 1794 novel, The Mysteries of Udolpho is a suitable example.) foreshadowing – omens and curses, settings such as gloomy castles, mountain regions, graveyards etc.

Supernatural Elements

While apparitions are characterised in a story to evoke fear or suspense, Wuthering Heights, a 430-page read, except at three or four instances, uses supernatural elements to mostly convey the psychological suffering of Heathcliff through his loss of Catherine.

(Few instances of supernatural occurrence in the story – after dozing off to sleep dreaming about Joseph, Lockwood experiences the presence of a ghost in Wuthering heights and is woken up by the rubbing of a branch of fir-tree against the window lattice. Also, when Nelly receives Heathcliff in a ‘ghastly paleness’, few days before his death or when Heathcliff recounts his ghostly encounter with Catherine’s spirit, and when after his death, people strongly believe that Heathcliff haunts the moors and Wuthering Heights.)

The Moors or the open fields

A silent but powerful link between the two households.

The emphasis on the moors in the story – wide, wild expanses but yet infertile lands – symbolise a linkage between the two households – Wuthering Heights and Thrushcross Grange, while also separating them from the rest of the village to give a feel of exclusivity, epitomizing the two homes as two major leads of the story – one as the hero and the other in a strong supportive role. The moors also represent Heathcliff and Catherine’s wild and free-spirited love.

The two houses, more than anything else, represent the temperament of their owners – one, God-fearing, peaceful and calm, similar to the description of his residence (Edgar – owner of Thrushcross Grange) and the other – owners of Wuthering Heights – one, a child of open lands and wilderness (Heathcliff) and the other, the epitome of aggression (Hindley).

Through through certain props in the setting of the story, Bronte has bridged the gap between the presence and physical absence of the leading characters to strengthen the plot.

Like the oak-paneled bed is symbolic of Catherine’s childhood, it symbolized also the isolated and secret life of Catherine when she hid from Heathcliff and wrote her journals, the corner of the bed dearest to her and provided comfort to the small girl escaping violence and searching for her expression. Towards the end of the story, Heathcliff too dies in the same bed with the window open, symbolizing that his spirit has escaped to become one with Catherine’s.

When Lockwood sees Catherine’s ghost through the same window, desperately wanting to come inside, it symbolized the fact that nobody can be spared loneliness in a place that belonged to someone, who so passionately sought its company that it seemed to be possessed by her eternally, even beyond her death.

The windows and the lattice

The windows and the lattice pervade the story as symbols of enclosure and entry of the elements of the world outside, especially the weather – sometimes alien but mostly resonating with the world within Wuthering Heights.

Weather as a prominent symbol in the story also describes the tumult within the hearts of its inhabitants – the characters have been firmly rooted in the natural images of their environment. The elementary forces of nature have been aptly used by the storyteller to introduce the readers to the changing landscapes of the characters’ emotions by way of narration and dialoguing.

Taking Nelly’s narration as an example when she described the night of Heathcliff’s departure from Wuthering Heights, we have this –

‘About midnight, while we still sat up, the storm came rustling over the Heights in full fury. There was a violent wind, as well as thunder, and either one or the other split a tree off at the corner of the building; a huge bough fell across the roof and knocked down a portion of the chimney-stack, sending a clatter of stones and soot into the kitchen fire.’

Wuthering Heights, during the time of its first release in 1847 was considered controversial on religious and moral grounds. But today it is one of the greatest classics in English literature. The symbolic devices the author uses to communicate the soulful love, wilderness and emotional turmoil of her lead characters, remain a subject of interest for many literature enthusiasts and language experts.

To me, the book, after three reads, has become a treasure to cherish and a tale to revisit, whenever the weather reminds me of Nelly narrating the intriguing story of Catherine and Heathcliff.

by Sneha Sharma | Mar 21, 2021 | Children's Literature

Photo Credit: Abir Sharma

When I first heard the story of Ferdinand in one of the Read Aloud Sessions arranged by a friend, it took me back to my own childhood. During recess, when kids were set free to frolic in the sand pit, I would stand against the bricked plant enclosures, some distance from the pit and would relish in the fragrance of the roses, wafting through them. There was also a desire to join the crowd but many times hesitation took the better of me and the allure of this heavenly fragrance made me reject the idea outright.

With time and support I overcame the hesitation but the fragrance of peace and solitude still fascinates me. I still prefer spending most of the time of quiet mornings and calming nights to myself in the good company of my books and laptop. And I have never regretted it!

The story of Ferdinand written by Munro Leaf is about a bull who hates bullfights and ultimately decides to remain peaceful and never participate in violence, after an experience in the ring which does not excite him. Instead, the smell of his favourite flowers at the centerstage sweeps him off his feet and he chooses to sit and savour it, right inside the ring.

True to his nature, Ferdinand, through the support of his mother who works infallibly on her motherly instincts, eventually learns to cherish the gift of his authenticity.

But is the story also pointing to a darker layer of human psyche that allures us to stay in our comfort zones, devoid of challenges?

After a careful study of the theme, the story seems to reassert the premise – necessitating the effort on the part of parents and teachers, of assuring that their children and protégé stay true to the beauty of their uniqueness and learn to assert it without fear. Contrary to what many believe about the message the story is silently conveying of anti-growth mindset and not stepping out of our comfortability, the bull in fact is challenged for his peaceful way of living but stays determined on his committal of being non-violent.

The story plays on a bigger moral – the lesson Morrie taught his student in ‘Tuesdays with Morrie’ –

‘Our culture does not make us feel good about ourselves. We are teaching the wrong things and you have to be strong enough to say that if the culture doesn’t work, don’t buy it. CREATE YOUR OWN. Most people can’t do it and so they remain unhappy.’

The very idea of a violent game with aggression as its fuel, worked fundamentally as a repellent to Ferdinand and so portrayed his authenticity and not cowardice.

Lesson 1 –

Lesson for kids –

Choosing to stand for your authenticity is truly liberating. (Authenticity – being legitimate and true to the self.)

Our men, since childhood, have been nurtured to believe that they should be tough. But how far does it take them towards the boundary, where toughness ends and aggression begins? Why have we forgotten that our young boys are after all children with a tender human heart and the fact that each has their own uniqueness; some being more sensitive than the others?

Lesson 2 –

Acceptance of variety and distinctiveness – as parents, as a society.

Ferdinand’s mother, initially apprehensive about her son’s distinct behavior and fearful that he might remain singled out, eventually discovers that he is happy and complacent, for he is being what he truly is – extension of his identity without being unethical or hurtful to someone else. She accepts him in his entirety. The story can question the capacity of a society as a unit to accept a distinct member, its inclusivity and integrity. It can question the member of a tribe about his sense of belongingness to his clan.

Lesson 3 –

The story also gives a perspective on an important underrated issue of animal oppression. The fact that being a member of a particular specie can obligate someone to perform a task a certain way, is questionable. The need to live and breathe freely applies to all.

Twentieth Century Fox partnered with PETA’s friends at animal sanctuary The Gentle Barn to create this “film, based on the original story by Leaf about misunderstood animals and their right to be free.”

Every year, thousands of bulls are killed within the deathly confines of the bullrings in the fights triggered by matadors and picadors. But for many of us, in love with this gentle bull hero, the good news is bullfights are now being banned in many nations and even former champion bullfighters are now speaking out against it.

Lesson 4 –

Dealing with Aggression

Ferdinand triggers a philosophical debate and questions the child reader about whether she would choose aggression as a response to an adversity or would adhere to ‘passive resistance’ or accommodate self-defense as a justified form of aggression?

Ahimsa has long been an identity of Indians. As Mahatma Gandhi’s pet weapon in driving Britishers out, as Martin Luther King’s philosophical motivation, it has taken hundreds of years for us to understand the significance of a non-violent settlement.

While most of our decisions can be driven by circumstance and can be intuitional, several studies and researches reveal the consequence of aggression, if unregulated – major mental disorders or poor social outcomes.

In the movie Ferdinand, taken from the story, the hero asks his father – “Is it possible to become a champion, without having to fight?’

In any case, we can easily imagine a regressive world – uncivilized and primitive, if we choose to live with aggression or teach our children to resort to it as a primary form of defense.

Ferdinand was BIG and STRONG but he did not let it equate to being AGGRESSIVE.

The story works on another important sub-theme of gender-stereotyping. Working on the same lines the story penned by Indian author Richa Jha, The ‘Unboy Boy’, features Gagan, considered ‘un-boy’ – ish for being peaceful and for not joining other boys in their violent pursuits. Ultimately his friends discover and applaud what he truly is – Brave, Adventurous and PEACEFUL.

The story of Ferdinand offers life lessons for adults more than children. It is the responsibility of the parents to teach their child, the difference in facing a challenge and standing true to his identity for he might confuse the two. And for this reason, it is imperative to understand the difference ourselves first.

For kids although it offers the lesson of celebrating one’s identity in a truly light-hearted, serene narration that is enjoyed by children of all age groups.

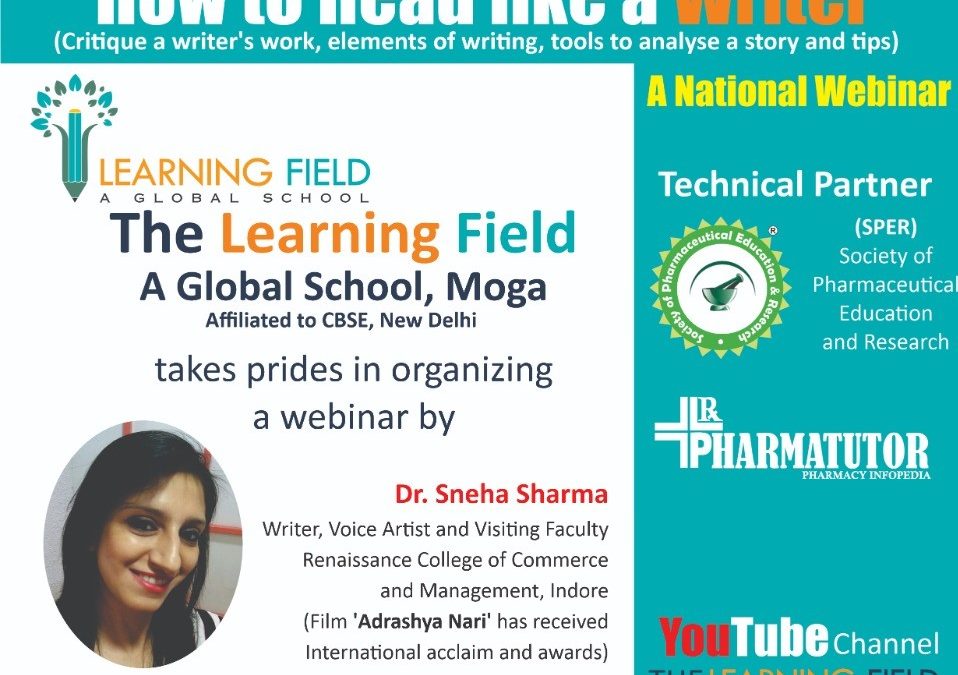

by Sneha Sharma | Jan 15, 2021 | Creative Writing Tips

Does the method of reading change, if we are a writer? Well, the answer is, it needs to, if we haven’t yet discovered the technique of RLW (Reading Like a Writer).

The first thing I try to teach in my writing workshops, to every new batch is the base point from where the journey of writing begins – and it has to be, by all means, the way we read!

My research and articles elaborating and analyzing this point, published in UGC approved journals and internal university periodicals, have put me in a position to elaborate on the main points of the techniques of reading.

Mike Bunn in one of his chapters in Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing (Volume 2), explains the importance of RLW. He uses Allan Tate’s metaphor of writing, when one thinks of herself as an architect, understating like a student, the constructs of ‘building’ a story, so that one can build it for herself.

A writer is “a reader moved to emulation.”

In a Paris Review interview, when asked if his earlier work has been inspired by Virginia Woolf, author William Maxwell (Author of ‘So Long, See You Tomorrow’ and ‘They came Like Swallows’) agreed that his earlier work indeed was a compendium of all of his favorite authors. He quoted another legend Saul Bellow as saying,

“A writer is a reader who is moved to emulation.”

(To strive to equal or excel, especially through imitation. Eventually we find our voice as we keep on writing. )

Robert Peake in his article – Emulation, Originality, and the Writing Tradition, elaborates on how emulation–as defined by a desire to imitate and transcend the spirit and tactical successes of works one admires–can actually enhance originality.

Talking of emulation, I also like Robert’s idea of reading widely and responding genuinely to our rich heritage of literary arts. Maybe reading a thousand authors and then narrowing the reading down to a select few who are your favorites and exercising through imitation of their style of writing till the time we find our own independent voice as writers.

Emulation teaches you to creatively rewrite and re-examine the mechanics of what was written

Emulation can be thought for thought (rewriting the thought conveyed in a passage in your own words)or it can be a word for word (replacing the adjectives and nouns, for example, with other synonymous adjectives and nouns)

Many times, reading too much of the same author can automatically lead to writing like him.

Read Slow –

Understanding the usage of a language as a medium and its sentence structure is the key to become an eloquent writer. That would happen when we read slow to grasp the power and CHOICE of words used in popular literature.

Language is to a writer what notes is to a musician and color to a painter. The wonder of every piece of art is its intricacies, what went into it.

“Every page was once a blank page just as every word that appears on it now was not always there, but instead reflects the final result of countless large and small deliberations. All the elements of good writing, depend on the writer’s skill in choosing one word instead of another. And what grabs and keeps our interest has everything to do with those choices. It’s surprising how easily we lose sight of the fact that words are the raw material out of which literature is crafted.” – Francine Prose – Fifty Shades of Grey.

My absolute favourite suggestion –

Reread your old favorites –

When you read a book for the first time, you are busy comprehending the story, grasping the language, journeying the symbolism, making notes but after you become familiar with these constructs and like what you read, it is a good idea to re-experience it. It’s like going back to your summer house in vacations time and again, to relive the comfort of the place you enjoy so much being into.

Consider asking yourself – what is that one or two things about the book that made me come back to it?

- What makes the book special?

- Who was my favorite character?

- Is there anything to learn about the character arcs or kind of metaphorical references made for him/her?

For a passage you admire, you can choose to ask yourself –

- What was the word choice of the author?

- What was the rhythm?

- Is the passage offering any new perspective that is changing what the story has meant to me until now?

- Ruthanne Reid, author for ‘The Write Practice’ suggests – elaborating on the paragraph that you think is the game-changer of the story; something that made your perspective change about the character’s choices or emphasizes on the gravity of the problem or importance of the solution offered or why the character’s assumptions are such, maybe because she belongs to a different culture or locality. Talk about it.

Elaborate on these points in a notebook or a blog. Share with others or have a discussion group.

Also reading the same genre in which you are willing to write would help to evaluate which archetypes to avoid. Although reading across the genre helps boost creativity.

Helpful links –

Saul Bellow was a Canadian-American writer. For his literary work, Bellow was awarded the Pulitzer Prize, the Nobel Prize for Literature.

*1 – Ruthanne Reid writes in the blog ‘The Write Practice’ – ‘There is a rhythm to good prose writing. Read a beautiful passage out loud if you don’t believe me. If you were to swap words with synonyms of different syllable count, the rhythm would totally change.’